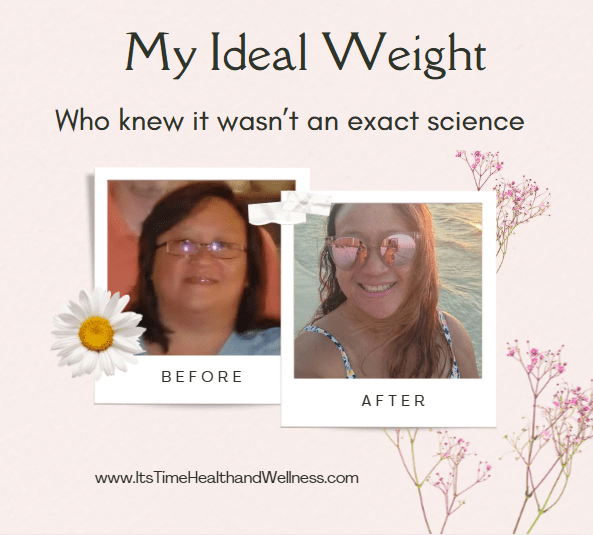

Who knew it wasn’t an exact science!

Why can’t I reach my ideal weight?

A person’s ideal weight is not an exact science because it depends on numerous individual factors that go beyond simple measurements like height and weight. Body composition, including muscle mass, fat distribution, and bone density, plays a significant role. A good example are athletes, they may have a higher weight due to muscle but still be very healthy. Age, genetics, sex, and overall health conditions also influence what a healthy weight looks like for each person. Tools like Body Mass Index (BMI) and Ideal Body Weight (IBW) formulas are only general references and do not account for these complexities. Research shows that people in the “overweight” BMI category can have lower health risks than those in the “normal” range, highlighting the limitations of using weight alone as a health indicator. Ultimately, health is best assessed through a combination of lifestyle habits, metabolic markers, fitness levels, and medical evaluations and not only a single number on a scale.

Focus on Health Outcomes and Functional Goals

While BMI is a widely used screening tool to estimate health risks based on height and weight, it should not be the sole focus of your health goals. A healthy BMI (18.5–24.9) is generally considered ideal for most adults, but it doesn’t account for muscle mass, body fat distribution, or individual factors like age, ethnicity, or overall fitness.

Instead of fixating on a specific ideal weight, focus on health outcomes and functional goals. Functional goals are specific, measurable objectives that focus on a person’s ability to perform real-life tasks and participate in everyday activities. Prioritize measures that better reflect metabolic health, such as:

- Waist circumference: Less than 35 inches for women and 40 inches for men (or less than half your height)

- Waist-to-height ratio: Waist circumference divided by body height, both measured in the same units

- Body fat percentage: Under 30% for women and 25% for men.

- Lifestyle habits: Regular physical activity, balanced nutrition, and managing blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar

Even small weight losses about 5–7% of body weight can significantly improve health markers like blood sugar and blood pressure. Ultimately, the goal is not just a number on the scale, but improved well-being, energy, and reduced risk of chronic disease. Consult your healthcare provider prior to starting a weight loss program to ensure your safety. When ready for a personalized assessment that goes beyond BMI, get started with Rose@ItsTimeHealthandWellness.com. Feel free to create your complimentary profile along with a complimentary Initial Consultation.

Muscle Mass and Weight

Muscle mass significantly affects ideal weight calculations because muscle is denser than fat, meaning it weighs more per unit of volume. This impacts common metrics like BMI, which only considers height and weight, not body composition. As a result, a muscular person may be classified as “overweight” or “obese” by BMI standards despite having low body fat and excellent health.

For example, research shows that athletes often have high BMIs due to muscle mass, not excess fat, leading to misclassification. Muscle also influences metabolism, more muscle increases resting calorie burn, supporting metabolic health even if weight is higher. Conversely, low muscle mass, even at a “normal” weight, is linked to higher risks of diabetes, heart disease, and mortality.

Muscle mass directly increases Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) because muscle is metabolically active tissue, requiring energy even at rest. Skeletal muscle is a major determinant of RMR, which accounts for 60–70% of daily energy expenditure. More muscle means a higher baseline calorie burn, supporting long-term weight management and metabolic health.

Metabolism

Metabolism refers to a set of life sustaining chemical reactions that occur within living organisms. These reactions are essential for converting food into energy, building and repairing tissues, and eliminating waste products. Metabolism encompasses all biochemical processes in the body, including digestion, energy production, and the synthesis of molecules like proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.

At the cellular level, metabolism consists of two main processes:

- Catabolism: The breakdown of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) into simpler forms (like glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids) to release energy.

- Anabolism: The use of energy to build complex molecules from simpler ones, such as synthesizing proteins from amino acids or storing glucose as glycogen.

These reactions are catalyzed by enzymes and are tightly regulated to maintain homeostasis, the body’s internal balance. Metabolism powers vital functions like breathing, circulation, cell repair, and brain activity, and it never stops, even during rest or sleep. The rate at which the body uses energy is called the metabolic rate, influenced by factors such as age, sex, muscle mass, physical activity, and hormones.

Differences Between BMR and RMR

Your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) is the minimum amount of calories your body requires to perform essential functions. It includes digestion, breathing, temperature stabilization, hair & skin growth, maintenance of different chemicals, and pumping blood in your body. BMR burns about 70% of your caloric intake in a 24-hour cycle. The rest of the calories can be used in exercising, and activities of daily living.

While you are resting, your body needs energy to function. This is called Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR). These are the low effort daily activities such as eating, walking for a short period, using the bathroom, drinking caffeine, sweating or shivering.

With regards to fitness, BMR and RMR both provides an idea of your overall metabolism. Higher metabolic activity indicates your body burns higher calories daily. Physically fit individuals have a higher rate of both BMR and RMR.

Total Daily Energy Expenditure

It’s important to mention your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This is the total amount of calories burned daily. TDEE includes calories burned through rest, exercise and digestion. Your calories at rest can be represented by either BMR or RMR. Their amounts are very similar.

Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE) and Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) are effectively the same concept, used interchangeably in nutritional and physiological contexts.

- TDEE specifically refers to the total number of calories burned by the body in a 24-hour period.

- TEE is the broader scientific term for the same metric, representing the total energy expended over a day through all bodily functions.

Both terms include the same three main components:

- Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) – energy used for basic physiological functions (60–75% of TDEE/TEE).

- Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) – energy used to digest and process food (~10%).

- Activity Energy Expenditure (AEE) – energy burned through physical activity, including exercise and non-exercise (NEAT) activities.

While some sources use TDEE for practical, daily estimation (e.g., in weight management), TEE is often used in research and clinical settings. The distinction is largely semantic, not substantive.

Beyond Metabolism

Understanding your metabolism is helpful in customizing your workouts and nutritional needs. Most energy exchanges takes place in your muscles with regards to metabolism. BMR will increase concurrently with your increased muscle mass.

Greater muscle mass is linked to lower risks of chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Muscle acts as an endocrine organ, releasing myokines that improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and support organ function. Myokines are signaling molecules such as cytokines, peptides, and growth factors produced and released by skeletal muscle cells in response to muscle contractions during physical activity.

However, in aging or ill individuals, low muscle mass (sarcopenia) is associated with frailty, higher RMR relative to body composition, and increased mortality, suggesting that elevated RMR in these cases reflects metabolic inefficiency or stress rather than health. Thus, while muscle generally boosts metabolic efficiency and longevity, an abnormally high RMR in older adults may signal underlying disease.

Nutrition

To lose weight, consuming less calories is necessary daily. However, knowing your RMR will help establish a personalized calorie baseline for a healthy weight loss. Consuming fewer calories than your RMR can lead to nutrient deficiencies and will result in metabolic slowdown. Metabolic slowdown is a key cause of weight loss plateau, but they are not the same thing.

A weight loss plateau refers to the halt or significant slowdown in weight loss despite consistent effort, while metabolic slowdown describes the physiological process where your body burns fewer calories due to weight loss and reduced energy intake. It is a key physiological mechanism that contributes to a weight loss plateau. This slowdown occurs through several mechanisms: a lower Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR), reduced Thermic Effect of Food (TEF), decreased Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT), and lower energy expenditure from exercise referred to as Total Energy Expenditure (TEE). Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) in fitness refers to the total number of calories your body burns in a day, encompassing all physiological processes and physical activities. It is a key metric for managing weight, optimizing performance, and planning nutrition.

The body becomes more efficient at using calories, making it harder to maintain a calorie deficit. This adaptation is driven by evolutionary survival mechanisms to protect against starvation.

While metabolic slowdown is a major factor, it is not the only cause of a plateau. Other contributors include:

- Hormonal changes: Increased ghrelin (hunger hormone) and decreased leptin (satiety hormone) can increase appetite.

- Loss of muscle mass: Less metabolically active tissue reduces overall calorie burn.

- Behavioral adaptation: Unconscious reductions in movement or slight increases in calorie intake over time.

- Set point theory: The body may resist weight loss by trying to return to a genetically predetermined weight range.

In short, a weight loss plateau is the observed outcome, while metabolic slowdown is one of the primary biological reasons behind it. Not all plateaus are due to metabolic slowdown—some are due to noncompliance, water retention, or changes in body composition (e.g., muscle gain). However, when a plateau persists despite consistent effort, metabolic adaptation is a likely contributor.

This adaptation is known as adaptive thermogenesis, a natural survival response that makes further weight loss harder. When the calorie deficit is eliminated due to metabolic slowdown, weight loss stalls resulting in a plateau. While metabolic slowdown is a major contributor, plateaus can also stem from noncompliance, hormonal changes, stress, poor sleep, or the body’s “set point” theory, which suggests it resists changes to a preferred weight. In short, metabolic slowdown is a primary reason for a plateau, but a plateau can also result from other factors.

Foods and Habits That Help Prevent Metabolic Slowdown

Consuming adequate protein helps preserve lean muscle mass during weight loss and increases the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF), meaning your body burns more calories digesting protein than carbs or fats. Protein intake helps preserve muscle during weight loss by providing amino acids that support muscle maintenance and reduce breakdown. When in a calorie deficit, the body may break down muscle for energy, but adequate protein intake ensures amino acids are available to sustain muscle tissue rather than being pulled from it.

Research shows that higher protein diets (1.2–1.6 g/kg or 0.45–0.73 g/lb of body weight per day) help preserve lean mass during weight loss, especially when combined with resistance training. For example, a 150 lb person should aim for 68–110 g of protein daily. Protein also increases satiety and slightly boosts metabolism through the thermic effect of food. However, protein alone isn’t enough, resistance exercise is essential to signal the body to retain muscle. Without it, even high protein intake may not fully prevent muscle loss.

- Aim for 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily from sources like chicken, fish, eggs, Greek yogurt, tofu, and legumes.

- Diets rich in whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and fiber support metabolic health. Replacing refined grains with whole grains has been shown to modestly increase resting metabolic rate (RMR).

- Drastically cutting calories signals starvation, causing your body to conserve energy and slow metabolism. Instead, aim for a modest deficit, reducing intake by 200–300 calories per day—combined with increased activity.

- Skipping meals or going for long periods without eating can slow metabolism. Eating every 3–4 hours helps maintain metabolic activity and prevents “starvation mode.”

- Muscle tissue burns more calories at rest than fat. Resistance training (e.g., weight lifting) helps maintain or build muscle mass, supporting a higher resting metabolic rate.

- Even mild dehydration can reduce metabolic efficiency.

In addition to formal exercise, increase your NEAT like standing, walking, or taking the stairs to burn more calories daily.

Bone Health

Therefore, ideal weight should consider body composition, including muscle-to-fat ratio, rather than relying solely on total weight or BMI. Tools like a Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan provide accurate muscle and fat measurements, offering a clearer health picture than the scale alone. DEXA scan is also known as a bone density scan, a low dose X-ray test that can measure bone mineral density to assess bone strength and diagnose conditions like osteoporosis. It is considered as a gold standard for evaluating fracture risk especially in postmenopausal women, older adults, and those with risk actors such as low body weight, etc.

Beyond bone health, a full body DEXA scan provides detailed body composition analysis, including body fat percentage, lean muscle mass, visceral fat (deep abdominal fat linked to heart disease and diabetes) as well as bone density. Athletes and others who are focused on weight management and their overall health can benefit from this precise repeatable tracking of data progress over time. Results are reported as T-scores (compared to young adult peak bone density) and Z-scores (compared to age- and sex-matched peers). A T-score of -2.5 or lower indicates osteoporosis.

It turns out that a person’s ideal weight is not an exact science because it depends on numerous individual factors that go beyond simple measurements like height and weight. Our body composition plays a significant role. Age, genetics, sex, and overall health conditions also influence what a healthy weight looks like for each person. Lifestyle habits also contributed from eating proper nutrition regularly, paying attention to activities of daily living, avoiding starvation or skipping meals, resistance training to build or maintain muscle mass, and focusing on health outcomes using functional goals.

Key takeaway

A plateau is not a failure, it’s a sign your body has adapted. Addressing it requires adjusting calorie intake, exercise, or both, while managing hunger and stress.

Poor sleep increases cortisol and disrupts hunger hormones (ghrelin and leptin), which can slow metabolism. Aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep nightly and practice stress-reduction techniques like meditation or deep breathing.